IS Navigation: Researchers

Welcome to implementation science (IS) navigation for researchers. Here you will find the core elements of implementation research (IR) studies, expert advice from our IR team, and action steps to help design and carry out an IR study.

What Is This?

This page provides guidance around developing a complete implementation research (IR) study. It walks users through identifying and specifying each of the necessary components of an IR study using a list of curated resources.

To browse all of our resources, check out our Resource Repository.

Who Is This Curriculum For?

This page is designed for researchers and/or practitioners with at least a basic understanding of IR (if not, see our IS Curriculum) and a potential IR project in mind. The sections briefly review each component, but focus more on specification of those components. Advanced knowledge of implementation science methods is not required.

How Do You Use the Curriculum?

For those newer to IR, the Components of an IR Study section provides an overview of the other sections. It also serves as a checklist for you as you develop your own study.

In each section, we share with you our expert advice and outline action steps to help you specify the relevant components.

Developing an IR study is rarely a linear process. Depending on your specific research question and context, you may jump around to different sections or revisit sections after gathering further information.

Curriculum Navigation

Components of an IR Study

- Overview

- The THING

- Implementation Partners

- Implementation Process and Implementation Gap

- Stage of IR

- Contextual Determinants

- Strategies & Mechanisms

- Implementation Outcomes

- Frameworks and the IR Logic Model

- Research Design

- Funding

Overview

Designing any research study requires the careful coordination of constructs, hypotheses, design(s), participants, measures, and so on. IR studies have added complexity because of their multilevel and often multisite nature, as well as having contextual factors to be controlled for or allowed to vary.

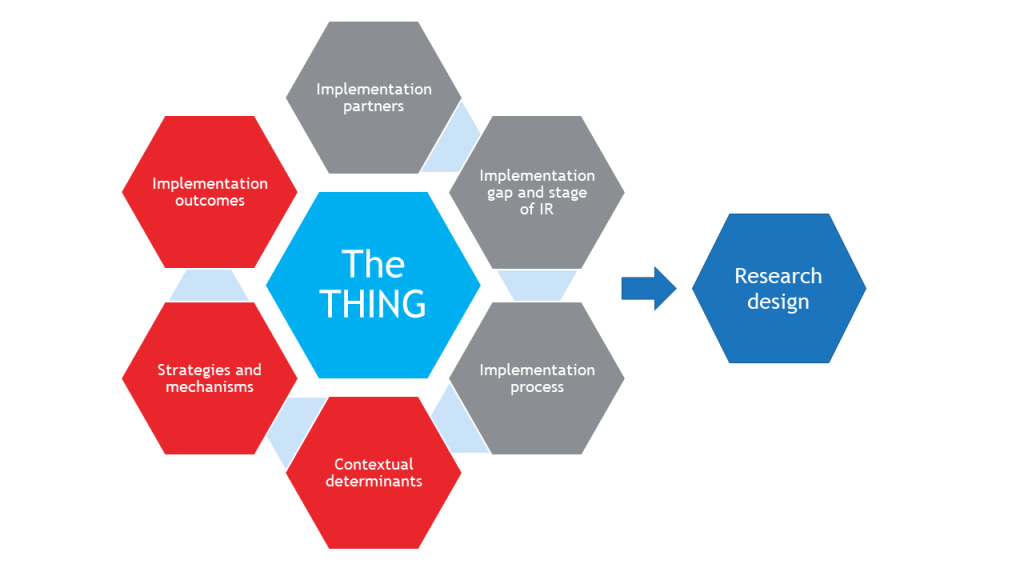

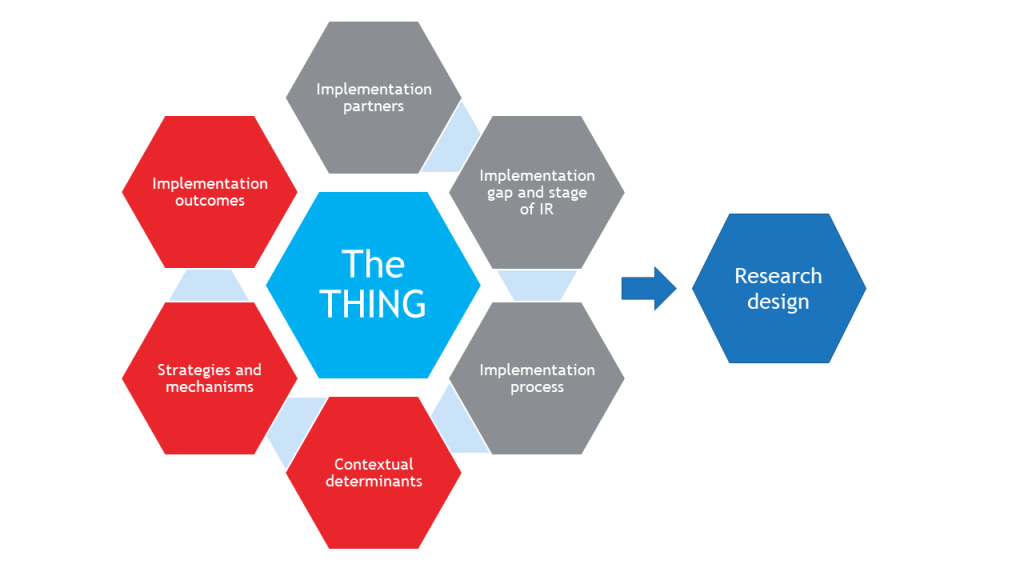

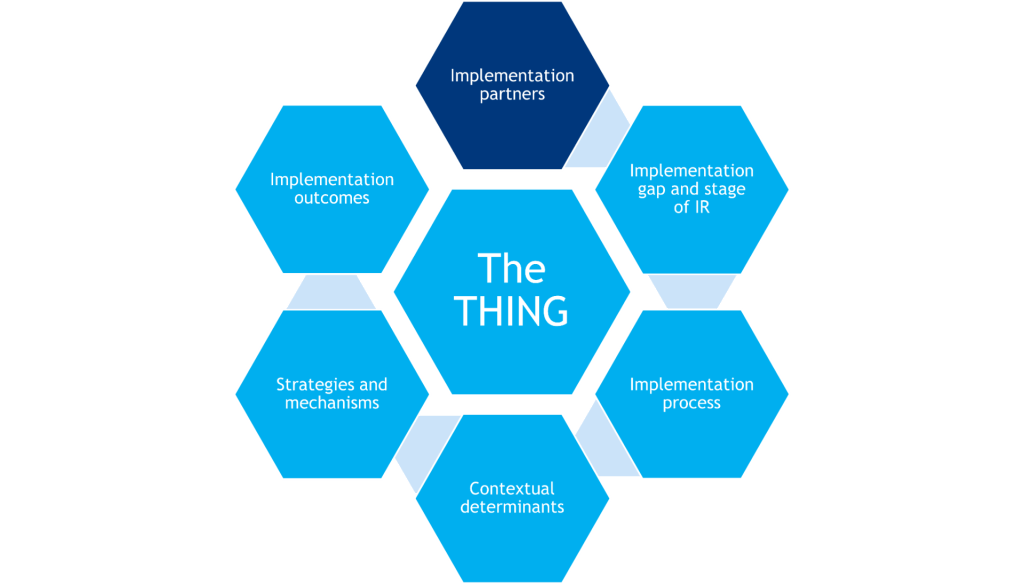

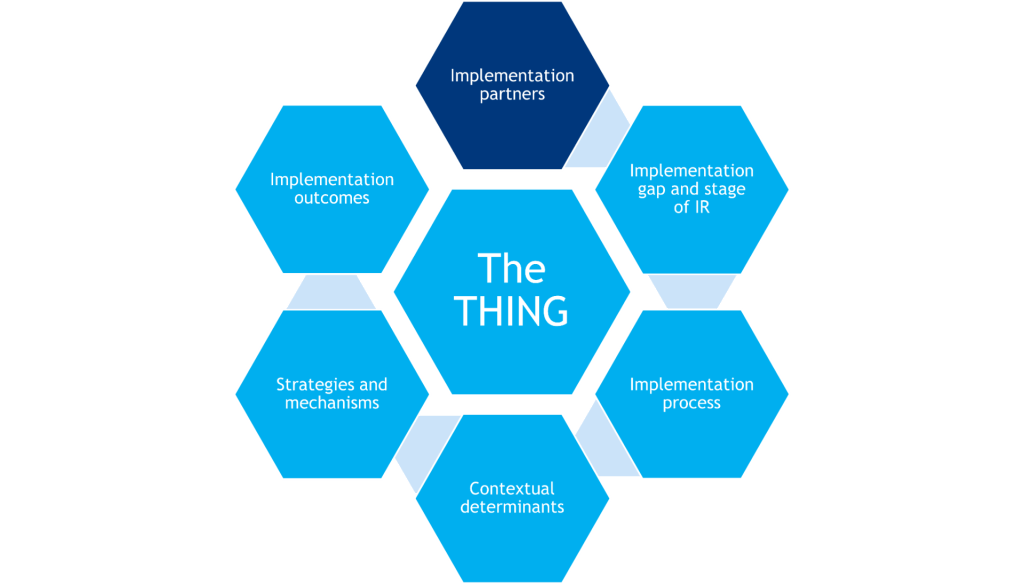

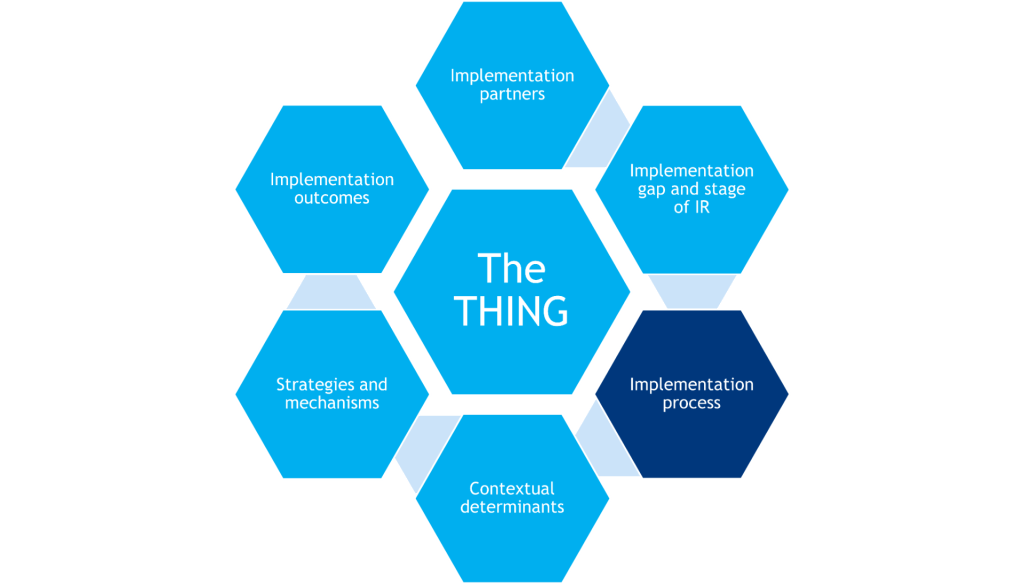

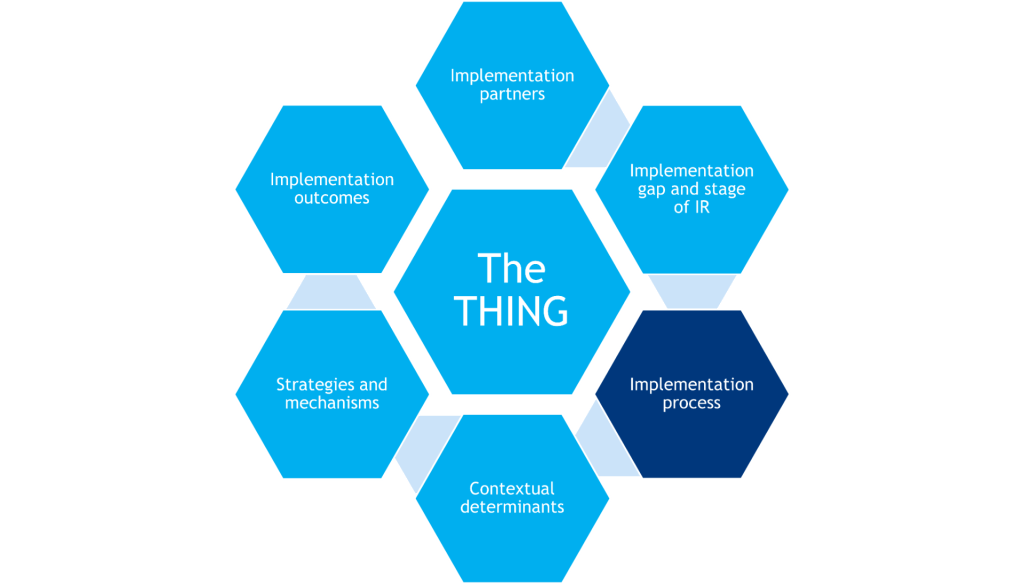

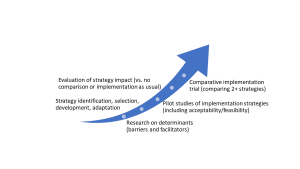

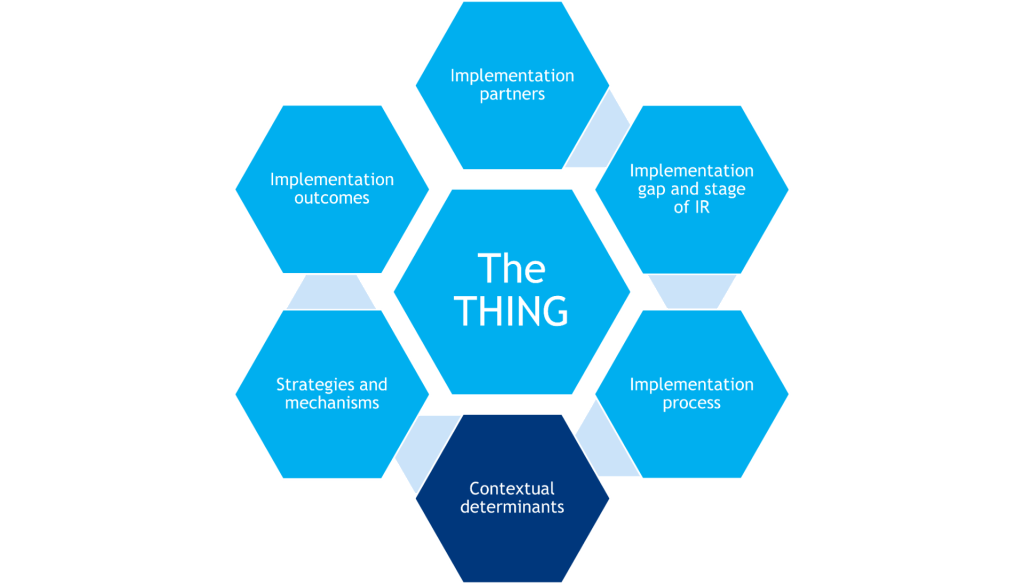

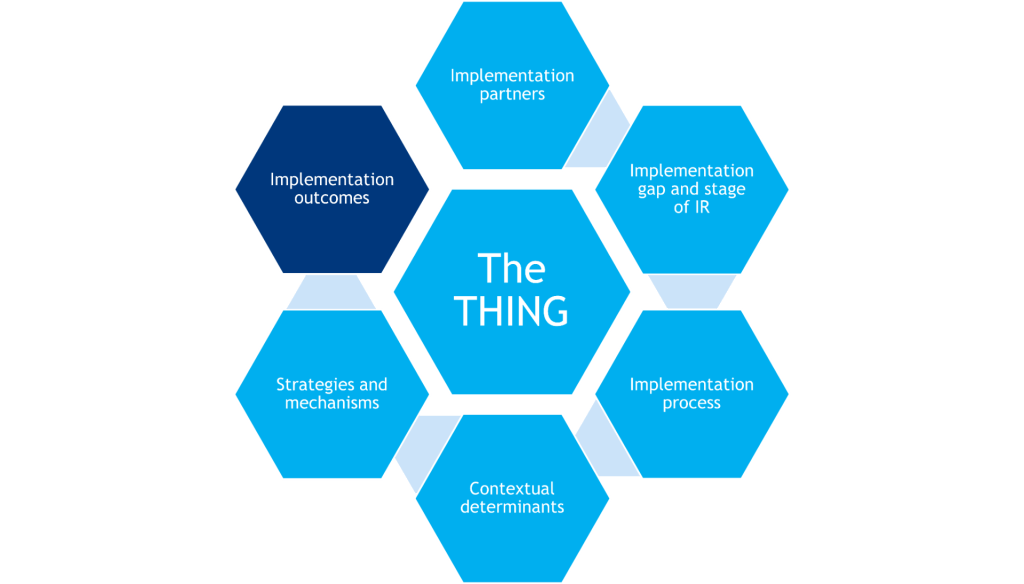

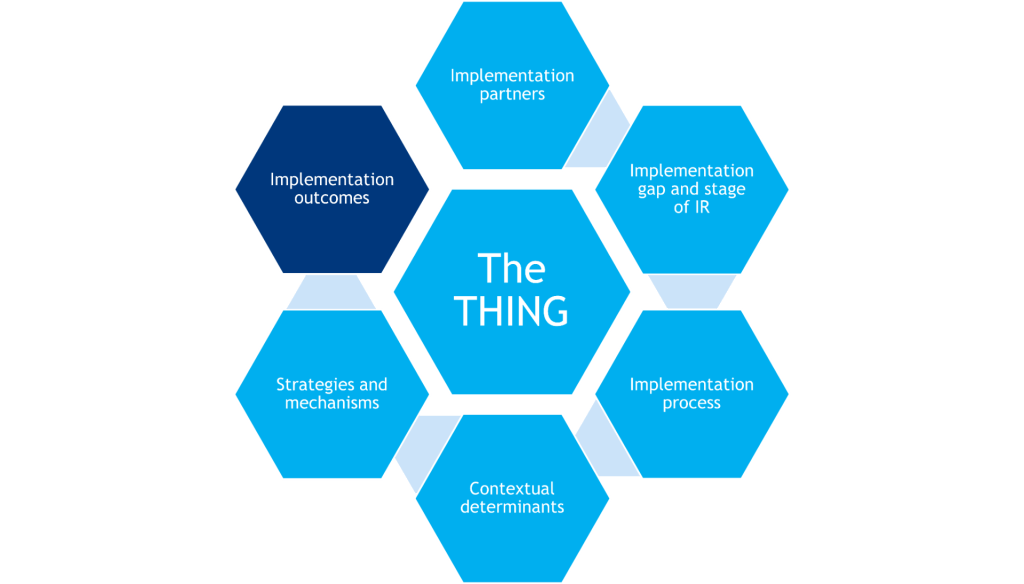

To plan an IR study, a researcher must consider and specify the following:

-

- The THING that is to be implemented (or improved upon, or de-implemented)

- Components that shape the background of the study (gray hexagons)

- Components that determine what will be measured in the study (red hexagons)

Together, these components inform the research design.

The THING

The evidence-based clinical or preventive intervention or practice, implementation strategy, policy, or other innovation that is to be implemented.

Implementation Partners

Individuals, communities, organizations, and agencies that are essential in the selection and implementation of the THING. Implementation partners operate within the healthcare delivery system, have implementation expertise and/or lived experienced that supports implementation of the THING.

Implementation Process and Implementation Gap

There are generalized steps to getting the THING adopted, implemented, and sustained within target implementation settings (i.e., putting the THING into practice). The implementation gap identifies where there is a disconnect in this process, which helps shape the focus of the research question(s).

Stage of IR and Implementation Process

Based on what is already known about implementation of the THING, further shapes the research question(s) and dictates study variables and measures, the number of sites and study participants, and study design complexity.

Contextual Determinants

Barriers and facilitators that help explain what implementation strategies work when, where, and/or why. May act as moderators or mediators of implementation success.

Strategies & Mechanisms

Activities or techniques used to enhance adoption, implementation, sustainment, and/or scaling of the THING that often target the healthcare delivery system and do not have a direct effect on clinical outcomes. Mechanisms are processes that explain how implementation strategies operate on determinants to affect one or more implementation outcomes.

Implementation Outcomes

Implementation outcomes are the effects of deliberate and purposive implementation strategies to implement the THING. Additionally, service outcomes are quality indicators of delivering the THING, and individual/clinical outcomes are the downstream effects on clients/patients after successfully implementing the THING.

Frameworks and the IR Logic Model

Implementation science contains countless theories, models, frameworks, and taxonomies (TMFTs) that help guide specification of one or more of the above components. The IR logic model helps combine and organize multiple TMFTs in a study.

Research Design

The structure of the research study (e.g., methods, unit of analysis, randomization assignment, data collection points) used to systematically explore, examine, or evaluate implementation of the THING within target implementation settings.

Funding

Ways to financially support (studying) implementation of the THING within target implementation settings.

- Overview

- The THING

- Implementation Partners

- Implementation Process and Implementation Gap

- Stage of IR

- Contextual Determinants

- Strategies & Mechanisms

- Implementation Outcomes

- Frameworks and the IR Logic Model

- Research Design

- Funding

Overview

Designing any research study requires the careful coordination of constructs, hypotheses, design(s), participants, measures, and so on. IR studies have added complexity because of their multilevel and often multisite nature, as well as having contextual factors to be controlled for or allowed to vary.

To plan an IR study, a researcher must consider and specify the following:

-

- The THING that is to be implemented (or improved upon, or de-implemented)

- Components that shape the background of the study (gray hexagons)

- Components that determine what will be measured in the study (red hexagons)

Together, these components inform the research design.

The THING

The evidence-based clinical or preventive intervention or practice, implementation strategy, policy, or other innovation that is to be implemented.

Implementation Partners

Individuals, communities, organizations, and agencies that are essential in the selection and implementation of the THING. Implementation partners operate within the healthcare delivery system, have implementation expertise and/or lived experienced that supports implementation of the THING.

Implementation Process and Implementation Gap

There are generalized steps to getting the THING adopted, implemented, and sustained within target implementation settings (i.e., putting the THING into practice). The implementation gap identifies where there is a disconnect in this process, which helps shape the focus of the research question(s).

Stage of IR and Implementation Process

Based on what is already known about implementation of the THING, further shapes the research question(s) and dictates study variables and measures, the number of sites and study participants, and study design complexity.

Contextual Determinants

Barriers and facilitators that help explain what implementation strategies work when, where, and/or why. May act as moderators or mediators of implementation success.

Strategies & Mechanisms

Activities or techniques used to enhance adoption, implementation, sustainment, and/or scaling of the THING that often target the healthcare delivery system and do not have a direct effect on clinical outcomes. Mechanisms are processes that explain how implementation strategies operate on determinants to affect one or more implementation outcomes.

Implementation Outcomes

Implementation outcomes are the effects of deliberate and purposive implementation strategies to implement the THING. Additionally, service outcomes are quality indicators of delivering the THING, and individual/clinical outcomes are the downstream effects on clients/patients after successfully implementing the THING.

Frameworks and the IR Logic Model

Implementation science contains countless theories, models, frameworks, and taxonomies (TMFTs) that help guide specification of one or more of the above components. The IR logic model helps combine and organize multiple TMFTs in a study.

Research Design

The structure of the research study (e.g., methods, unit of analysis, randomization assignment, data collection points) used to systematically explore, examine, or evaluate implementation of the THING within target implementation settings.

Funding

Ways to financially support (studying) implementation of the THING within target implementation settings.

Defining the THING to Be Implemented

What it is

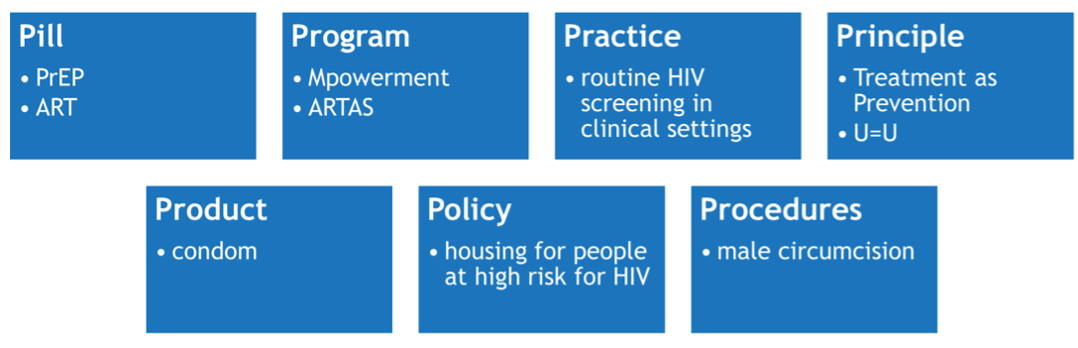

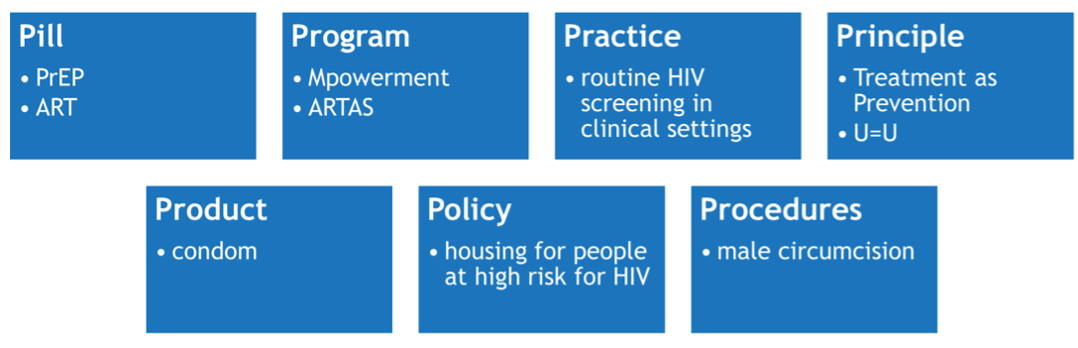

All IR is anchored to a THING (Curran, 2020) that is being introduced or improved upon in a delivery setting. The THING is typically a preventive, clinical, or educational intervention or innovation with established effectiveness of directly changing a proximal health outcome – i.e., HIV transmission/acquisition risk or viral suppression. But, the THING can also be a novel implementation strategy being introduced.

Brown et al. (2017) describes seven types of THINGs, with examples from HIV:

Expert advice

The THING is a relative label given to what is being implemented. It is defined in the context of a particular IR study.

The THING should be evidence-based, meaning prior research has shown that it is effective at improving a desired outcome (e.g., HIV knowledge, care utilization, viral suppression). However, there may be exceptions, such as when there is political will or an urgent need to implement a THING without traditional levels of evidence (e.g., COVID vaccinations).

Action items

-

- Define the THING to be implemented with your implementation partners.

- Describe the evidence you have thus far to support your THING’s implementation. If you do not have any evidence, you may not yet be ready to implement.

- Determine whether the THING itself needs to be adapted for your context (usually with input from the target population and/or implementation partners). If yes, continue to Adapting the THING.

Adapting the THING

An evidence-based THING may need to be culturally, developmentally, or otherwise adapted to a particular context or community before it can be implemented. Well-planned adaptations can strengthen intervention effects and/or improve implementability and sustainability.

Expert advice

Prepare and plan for some level of adaptions guided by a model or framework. It is more common to need adaptions than to not need them.

Generally, there are two places where adaptions can be made: 1) before formal testing of an adapted THING, typically as part of a pilot trial or 2) as part of a first phase of an IR study. Selecting when to make adaptions will be influenced in large part by the funding at your disposal.

Action items

-

- Use a framework like ADAPT-ITT (Wingood & DiClimente, 2008) or Intervention Mapping (Highfield et al., 2015) to systematically guide the adaptation of your THING. If your THING involves technology (e.g., eHealth, mHealth), also use the TIPs framework (Mohr et al., 2015) to differentiate the technological instantiation components that are adaptable from the intervention principles that are not.

- Document your adaptations using FRAME (Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2019).

- Determine how much research evidence you can “borrow strength” from to make the case that the THING will still be effective once adapted for a new population, new setting, or both (see Aarons et al., 2017). Conversely, determine what new evidence you will now need to demonstrate effectiveness.

What it is

All IR is anchored to a THING (Curran, 2020) that is being introduced or improved upon in a delivery setting. The THING is typically a preventive, clinical, or educational intervention or innovation with established effectiveness of directly changing a proximal health outcome – i.e., HIV transmission/acquisition risk or viral suppression. But, the THING can also be a novel implementation strategy being introduced.

Brown et al. (2017) describes seven types of THINGs, with examples from HIV:

Expert advice

The THING is a relative label given to what is being implemented. It is defined in the context of a particular IR study.

The THING should be evidence-based, meaning prior research has shown that it is effective at improving a desired outcome (e.g., HIV knowledge, care utilization, viral suppression). However, there may be exceptions, such as when there is political will or an urgent need to implement a THING without traditional levels of evidence (e.g., COVID vaccinations).

Action items

-

- Define the THING to be implemented with your implementation partners.

- Describe the evidence you have thus far to support your THING’s implementation. If you do not have any evidence, you may not yet be ready to implement.

- Determine whether the THING itself needs to be adapted for your context (usually with input from the target population and/or implementation partners). If yes, continue to Adapting the THING.

Adapting the THING

An evidence-based THING may need to be culturally, developmentally, or otherwise adapted to a particular context or community before it can be implemented. Well-planned adaptations can strengthen intervention effects and/or improve implementability and sustainability.

Expert advice

Prepare and plan for some level of adaptions guided by a model or framework. It is more common to need adaptions than to not need them.

Generally, there are two places where adaptions can be made: 1) before formal testing of an adapted THING, typically as part of a pilot trial or 2) as part of a first phase of an IR study. Selecting when to make adaptions will be influenced in large part by the funding at your disposal.

Action items

-

- Use a framework like ADAPT-ITT (Wingood & DiClimente, 2008) or Intervention Mapping (Highfield et al., 2015) to systematically guide the adaptation of your THING. If your THING involves technology (e.g., eHealth, mHealth), also use the TIPs framework (Mohr et al., 2015) to differentiate the technological instantiation components that are adaptable from the intervention principles that are not.

- Document your adaptations using FRAME (Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2019).

- Determine how much research evidence you can “borrow strength” from to make the case that the THING will still be effective once adapted for a new population, new setting, or both (see Aarons et al., 2017). Conversely, determine what new evidence you will now need to demonstrate effectiveness.

Engaging Implementation Partners

What it is

IR happens in the real world, not controlled laboratory environments, so researchers must have partners within and adjacent to the healthcare delivery system who are willing to implement and support implementation of the THING. These can include clinicians/providers, support staff, organization leaders, members of the client/patient populations, and other stakeholders in the implementation setting. IR proposals reviewed by the NIH often require implementation partners to be identified (e.g., through letters of support, NIH biosketches) and a plan that lays out what role they will have in the IR.

Expert advice

If you do not have implementation partners on your team, you cannot proceed with an IR study. However, engagement with partners exists on a continuum (Boyer et al., 2018), and different levels of engagement may be appropriate for different stages of IR:

(from Boyer et al., 2018)

IR has not always focused on making systems-level changes that are needed for implementation of EBPs. This is due in part to the methods that are typically used to design rigorous studies (e.g., using race to explain effects of EBPs on health outcomes) and the lack of variety in research teams that receive sponsored funding.

Engaging implementation partners and building trusting relationships using well-tested methods, like community-engaged research methods, increases the opportunities to address system-level factors (e.g., systematic racism and white supremacy) that influence consistent implementation of the THING.

Action items

-

- Identify your primary implementation partner(s), and work with them to identify their appropriate/desired level of engagement in the research. Refer to Boyer (2018) for guidance.

- Throughout your IR project, engage your partners with rigorous methods (https://dicemethods.org/StakeholderEngagement) and best practices (https://dicemethods.org/Tool).

- Throughout your IR project, engage your partners with rigorous methods (https://dicemethods.org/StakeholderEngagement) and best practices (https://dicemethods.org/Tool).

What it is

IR happens in the real world, not controlled laboratory environments, so researchers must have partners within and adjacent to the healthcare delivery system who are willing to implement and support implementation of the THING. These can include clinicians/providers, support staff, organization leaders, members of the client/patient populations, and other stakeholders in the implementation setting. IR proposals reviewed by the NIH often require implementation partners to be identified (e.g., through letters of support, NIH biosketches) and a plan that lays out what role they will have in the IR.

Expert advice

If you do not have implementation partners on your team, you cannot proceed with an IR study. However, engagement with partners exists on a continuum (Boyer et al., 2018), and different levels of engagement may be appropriate for different stages of IR:

(from Boyer et al., 2018)

IR has not always focused on making systems-level changes that are needed for implementation of EBPs. This is due in part to the methods that are typically used to design rigorous studies (e.g., using race to explain effects of EBPs on health outcomes) and the lack of variety in research teams that receive sponsored funding.

Engaging implementation partners and building trusting relationships using well-tested methods, like community-engaged research methods, increases the opportunities to address system-level factors (e.g., systematic racism and white supremacy) that influence consistent implementation of the THING.

Action items

-

- Identify your primary implementation partner(s), and work with them to identify their appropriate/desired level of engagement in the research. Refer to Boyer (2018) for guidance.

- Throughout your IR project, engage your partners with rigorous methods (https://dicemethods.org/StakeholderEngagement) and best practices (https://dicemethods.org/Tool).

- Throughout your IR project, engage your partners with rigorous methods (https://dicemethods.org/StakeholderEngagement) and best practices (https://dicemethods.org/Tool).

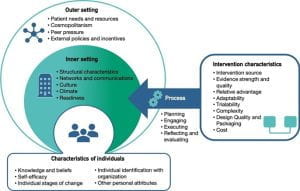

Planning the Implementation Process and Describing the Implementation Gap

What it is

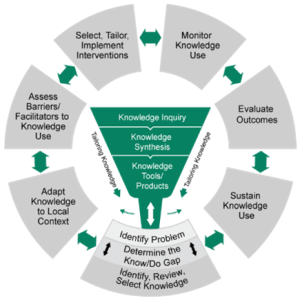

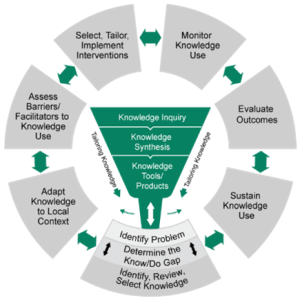

The implementation process refers to the steps needed to get the THING adopted, implemented, and sustained within target implementation settings (e.g., putting the THING into practice). Process models – one type of implementation science framework – provide a “road map” for implementation researchers and practitioners, identifying what actions to take and decisions to make at different time points.

Two of the most commonly used process models are the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS; ) framework and the Knowledge-to-Action (KTA; Field et al., 2014; pictured) framework.

(from Field et al., 2014)

Expert advice

-

- There are other process models besides EPIS and KTA, which may be better suited to your context (e.g., the CHAMPSS model focuses on schools). You can find explore other models here: dissemination-implementation.org. Note that process models generally follow a similar path, so if using one, pick one that best suits your purpose.

- Regardless of process model, plan out how implementation partners and other key stakeholders might be involved throughout implementation. A good example is the Dynamic Adaptation Process (Aarons et al., 2012), which builds off EPIS.

- Because implementation processes inherently require time, one IR study usually cannot study every step. Thus, it is important to identify where in the process your focus is.

- Implementation process is closely related with stage of IR. Click here to jump to this section.

- If you are interested in studying the process itself, the Stages of Implementation Completion is both a process model and measurement tool to do so.

Action items

-

- As applicable, select a process model for your IR study (dissemination-implementation.org) OR identify what step(s) your study will focus on.

Implementation gap

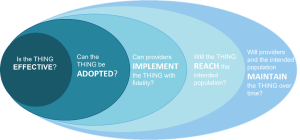

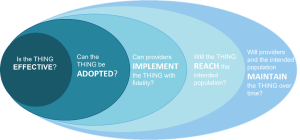

The implementation gap is a disconnect in the implementation process, otherwise thought of as the space between ideal implementation of the THING and what currently happens in practice. Understanding where there is a breakdown helps shape the focus of the IR question(s) that need to be addressed. An example of possible gaps, using the RE-AIM framework, is:

Expert advice

There may be many potential implementation gaps, and one IR study usually cannot address all of them. Thus, it is important to identify what gap your IR study is focused on.

The implementation gap is closely related to implementation outcomes. Click here to jump to this section.

Below is a list of conditions to that correlate to potential gaps. This list is not exhaustive, but covers areas targeted by a majority of IR studies.

| Condition | Potential Gaps |

| You do not have evidence that the THING will work to achieve the desired individual health outcomes | Intervention efficacy/effectiveness gap |

| If you adapted the THING, you do not have evidence (direct or “borrowed”; see Aarons et al., 2017) that the adapted THING will work similarly to the original | Adaptation effectiveness gap |

| Deliverers (e.g., clinics, organizations, individual providers) do not know about the THING | Deliverer dissemination gap |

| Delivers do not find the THING acceptable, and/or they do not want to use it | Adoption gap |

| Deliverers do not know how to implement the THING properly | Deliverer skill gap |

| Deliverers do not implement the THING as prescribed and/or with quality | Fidelity gap |

| Recipients (e.g., patients, clients) do not know about the THING | Recipient dissemination gap |

| Recipients do not find the THING acceptable, and/or they do not want to use it | Recipient uptake gap |

| Recipients do not know how to use the THING, and/or they stop using it prematurely | Recipient use/adherence gap |

| Deliverers do not continue implementing the THING over time | Deliverer sustainment gap |

| Recipients do not continue using the THING over time | Recipient sustainment gap |

Action items

-

- Describe the implementation gap based on what is known from the literature on implementation of the THING and on discussions with implementation partners about what they understand the gap to be in their context(s).

- Describe the implementation gap based on what is known from the literature on implementation of the THING and on discussions with implementation partners about what they understand the gap to be in their context(s).

What it is

The implementation process refers to the steps needed to get the THING adopted, implemented, and sustained within target implementation settings (e.g., putting the THING into practice). Process models – one type of implementation science framework – provide a “road map” for implementation researchers and practitioners, identifying what actions to take and decisions to make at different time points.

Two of the most commonly used process models are the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS; ) framework and the Knowledge-to-Action (KTA; Field et al., 2014; pictured) framework.

(from Field et al., 2014)

Expert advice

-

- There are other process models besides EPIS and KTA, which may be better suited to your context (e.g., the CHAMPSS model focuses on schools). You can find explore other models here: dissemination-implementation.org. Note that process models generally follow a similar path, so if using one, pick one that best suits your purpose.

- Regardless of process model, plan out how implementation partners and other key stakeholders might be involved throughout implementation. A good example is the Dynamic Adaptation Process (Aarons et al., 2012), which builds off EPIS.

- Because implementation processes inherently require time, one IR study usually cannot study every step. Thus, it is important to identify where in the process your focus is.

- Implementation process is closely related with stage of IR. Click here to jump to this section.

- If you are interested in studying the process itself, the Stages of Implementation Completion is both a process model and measurement tool to do so.

Action items

-

- As applicable, select a process model for your IR study (dissemination-implementation.org) OR identify what step(s) your study will focus on.

Implementation gap

The implementation gap is a disconnect in the implementation process, otherwise thought of as the space between ideal implementation of the THING and what currently happens in practice. Understanding where there is a breakdown helps shape the focus of the IR question(s) that need to be addressed. An example of possible gaps, using the RE-AIM framework, is:

Expert advice

There may be many potential implementation gaps, and one IR study usually cannot address all of them. Thus, it is important to identify what gap your IR study is focused on.

The implementation gap is closely related to implementation outcomes. Click here to jump to this section.

Below is a list of conditions to that correlate to potential gaps. This list is not exhaustive, but covers areas targeted by a majority of IR studies.

| Condition | Potential Gaps |

| You do not have evidence that the THING will work to achieve the desired individual health outcomes | Intervention efficacy/effectiveness gap |

| If you adapted the THING, you do not have evidence (direct or “borrowed”; see Aarons et al., 2017) that the adapted THING will work similarly to the original | Adaptation effectiveness gap |

| Deliverers (e.g., clinics, organizations, individual providers) do not know about the THING | Deliverer dissemination gap |

| Delivers do not find the THING acceptable, and/or they do not want to use it | Adoption gap |

| Deliverers do not know how to implement the THING properly | Deliverer skill gap |

| Deliverers do not implement the THING as prescribed and/or with quality | Fidelity gap |

| Recipients (e.g., patients, clients) do not know about the THING | Recipient dissemination gap |

| Recipients do not find the THING acceptable, and/or they do not want to use it | Recipient uptake gap |

| Recipients do not know how to use the THING, and/or they stop using it prematurely | Recipient use/adherence gap |

| Deliverers do not continue implementing the THING over time | Deliverer sustainment gap |

| Recipients do not continue using the THING over time | Recipient sustainment gap |

Action items

-

- Describe the implementation gap based on what is known from the literature on implementation of the THING and on discussions with implementation partners about what they understand the gap to be in their context(s).

- Describe the implementation gap based on what is known from the literature on implementation of the THING and on discussions with implementation partners about what they understand the gap to be in their context(s).

Staging the Implementation Research

What it is

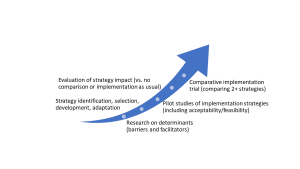

The stage of IR for your study places your IR question(s) on a continuum of IR complexity that in turn informs key aspects of the research design. It is closely related to the implementation process in that earlier-stage IR typically coincides with earlier process steps (e.g., research on determinants ~ exploration and preparation). Later-stage IR, which evaluates implementation strategies, requires that implementation partners are ready and prepared to implement the THING.

Smith et al. (2020) defined five stages of implementation research:

(from Smith et al., 2020)

Expert advice

-

- CFIR is not the only determinant framework and it is not a required framework for an IR study. Other examples include PRISM and the Theoretical Domains Framework.

- Consider the fit of a determinant framework to your field of study and your implementation context during selection.

- Individual-level determinants of HIV prevention and care are well known and in some cases overstudied. More research is needed to understand the intersection between structural determinants (eg., systematic racism), inner setting determinants (eg., provider views, clinic workflows), and facilitators for specific subgroups (eg., policies, organizational training and capacity). See article by Li et.al., 2022.

- The ISCI team is conducting systematic reviews of determinants and strategies for various HIV interventions in the United States. Visit our HIV Implementation Review Dashboard to access the latest systematic review data available from this project.

Expert advice

Each stage of IR can be applied to any type of implementation gap because different gaps are addressed by different strategies. For example, an adoption gap may require different strategies than a fidelity gap; for each gap, you could evaluate the same or different strategies moving up the stages of IR.

Your stage of IR is based on what is known or unknown about implementation of the THING. Below is a series of questions to help identify what stage your IR study might be at. If you answer “no” to the question, you might be at that stage. (The words that appear bolded in these questions are IR terminology, with the corresponding section linked for reference.)

|

Do you know what specific barriers and facilitators are affecting the specific implementation gap related to the THING? See: Understanding the implementation context |

Research on determinants |

|

Have you identified appropriate implementation strategies for the implementation gap related to the THING? See: Selecting implementation strategies |

Strategy identification, selection, development, adaptation |

|

If you have identified implementation strategies, do you know how effective they are at achieving implementation outcomes related to the implementation gap? See: Evaluating implementation success |

Pilot studies Evaluation of strategy impact |

| If you have effective implementation strategies, do you know how well it performs against alternative implementation strategies for addressing the implementation gap? | Comparative implementation |

Action items

-

- Identify the stage of your proposed IR study.

What it is

The stage of IR for your study places your IR question(s) on a continuum of IR complexity that in turn informs key aspects of the research design. It is closely related to the implementation process in that earlier-stage IR typically coincides with earlier process steps (e.g., research on determinants ~ exploration and preparation). Later-stage IR, which evaluates implementation strategies, requires that implementation partners are ready and prepared to implement the THING.

Smith et al. (2020) defined five stages of implementation research:

(from Smith et al., 2020)

Expert advice

-

- CFIR is not the only determinant framework and it is not a required framework for an IR study. Other examples include PRISM and the Theoretical Domains Framework.

- Consider the fit of a determinant framework to your field of study and your implementation context during selection.

- Individual-level determinants of HIV prevention and care are well known and in some cases overstudied. More research is needed to understand the intersection between structural determinants (eg., systematic racism), inner setting determinants (eg., provider views, clinic workflows), and facilitators for specific subgroups (eg., policies, organizational training and capacity). See article by Li et.al., 2022.

- The ISCI team is conducting systematic reviews of determinants and strategies for various HIV interventions in the United States. Visit our HIV Implementation Review Dashboard to access the latest systematic review data available from this project.

Expert advice

Each stage of IR can be applied to any type of implementation gap because different gaps are addressed by different strategies. For example, an adoption gap may require different strategies than a fidelity gap; for each gap, you could evaluate the same or different strategies moving up the stages of IR.

Your stage of IR is based on what is known or unknown about implementation of the THING. Below is a series of questions to help identify what stage your IR study might be at. If you answer “no” to the question, you might be at that stage. (The words that appear bolded in these questions are IR terminology, with the corresponding section linked for reference.)

|

Do you know what specific barriers and facilitators are affecting the specific implementation gap related to the THING? See: Understanding the implementation context |

Research on determinants |

|

Have you identified appropriate implementation strategies for the implementation gap related to the THING? See: Selecting implementation strategies |

Strategy identification, selection, development, adaptation |

|

If you have identified implementation strategies, do you know how effective they are at achieving implementation outcomes related to the implementation gap? See: Evaluating implementation success |

Pilot studies Evaluation of strategy impact |

| If you have effective implementation strategies, do you know how well it performs against alternative implementation strategies for addressing the implementation gap? | Comparative implementation |

Action items

-

- Identify the stage of your proposed IR study.

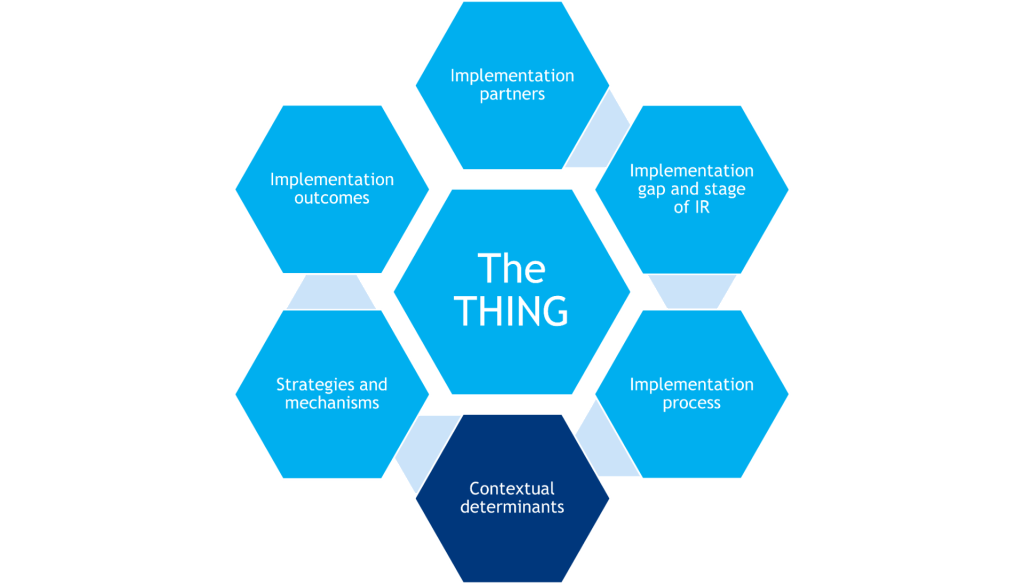

Understanding the Implementation Context (Determinants)

What it is

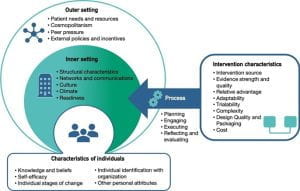

Context refers to the setting in a healthcare delivery system where the THING is delivered. This is where the identified implementation gap exists and where an IR question is studied.

Determinants of implementation are the (positive) facilitators and the (negative) barriers that help answer questions around why a THING works or fails and why an implementation strategy works or fails. Determinants help guide formative work in early steps of the implementation process and early stages of IR; in later stages of IR, determinants may also serve as moderators and mediators in analyses to understand implementation success.

The most widely used determinant framework to understand implementation context is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; pictured). CFIR is composed of 5 domains, each having its own unique set of constructs that may be explored in the implementation process.

For a full list of constructs, visit: https://cfirguide.org/constructs/

(Adapted from the Center from Implementation)

Expert advice

-

- CFIR is not the only determinant framework. Other commonly used models include PRISM and the Theoretical Domains Framework. You can find and explore other frameworks here: dissemination-implementation.org. Note that determinant frameworks generally have similar domains, so if using one, pick one that fits your field of study and your context.

- If you are using CFIR, note that the framework was recently updated. CFIR 2.0 was published in April 2022 and it includes guidance on using the proposed changes to the framework.

- Individual-level determinants of HIV prevention and care are fairly well known and, in some cases, overstudied. More research is needed to understand the intersection between structural determinants (e.g., systematic racism); inner setting determinants (e.g., provider views, clinic workflows); and facilitators for specific subgroups (e.g., policies targeting Latino individuals). See Li et.al. (2022) for an example.

- Mixed-method approaches (quantitative and qualitative) are the preferred way for assessing determinants.

- The ISCI team is conducting systematic reviews of determinants and strategies for various HIV interventions in the United States. Visit our HIV Implementation Review Dashboard to access the latest systematic review data available from this project.

Action items

-

- Select a determinant framework for your IR study.

- Begin to list out determinants that are known to your team, including those from the literature (use the HIV Implementation Review Dashboard).

- The IRLM can help you organize these (see section titled Using Conceptual Frameworks and the IRLM for more information on this tool).

- If applicable to your stage of IR, plan and prepare to collect determinants that are not known.

What it is

Context refers to the setting in a healthcare delivery system where the THING is delivered. This is where the identified implementation gap exists and where an IR question is studied.

Determinants of implementation are the (positive) facilitators and the (negative) barriers that help answer questions around why a THING works or fails and why an implementation strategy works or fails. Determinants help guide formative work in early steps of the implementation process and early stages of IR; in later stages of IR, determinants may also serve as moderators and mediators in analyses to understand implementation success.

The most widely used determinant framework to understand implementation context is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; pictured). CFIR is composed of 5 domains, each having its own unique set of constructs that may be explored in the implementation process.

For a full list of constructs, visit: https://cfirguide.org/constructs/

(Adapted from the Center from Implementation)

Expert advice

-

- CFIR is not the only determinant framework. Other commonly used models include PRISM and the Theoretical Domains Framework. You can find and explore other frameworks here: dissemination-implementation.org. Note that determinant frameworks generally have similar domains, so if using one, pick one that fits your field of study and your context.

- If you are using CFIR, note that the framework was recently updated. CFIR 2.0 was published in April 2022 and it includes guidance on using the proposed changes to the framework.

- Individual-level determinants of HIV prevention and care are fairly well known and, in some cases, overstudied. More research is needed to understand the intersection between structural determinants (e.g., systematic racism); inner setting determinants (e.g., provider views, clinic workflows); and facilitators for specific subgroups (e.g., policies targeting Latino individuals). See Li et.al. (2022) for an example.

- Mixed-method approaches (quantitative and qualitative) are the preferred way for assessing determinants.

- The ISCI team is conducting systematic reviews of determinants and strategies for various HIV interventions in the United States. Visit our HIV Implementation Review Dashboard to access the latest systematic review data available from this project.

Action items

-

- Select a determinant framework for your IR study.

- Begin to list out determinants that are known to your team, including those from the literature (use the HIV Implementation Review Dashboard).

- The IRLM can help you organize these (see section titled Using Conceptual Frameworks and the IRLM for more information on this tool).

- If applicable to your stage of IR, plan and prepare to collect determinants that are not known.

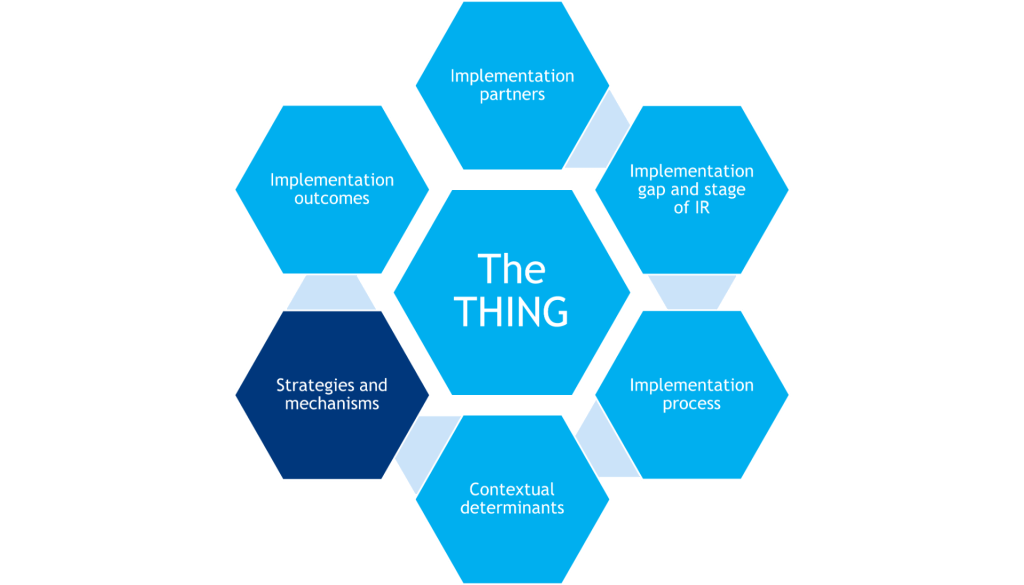

Selecting Implementation Strategies

What it is

Strategies are activities or techniques used to enhance adoption, implementation, sustainment, and/or scaling of the THING. In other words, strategies are the stuff one does to help other people and places do the evidence-based THING. They often target the healthcare delivery system, and they do not have a direct effect on clinical outcomes. They are the central focus of IR.

A discrete strategy is a single action or activity that can impact implementation. This is the smallest “unit” of strategies. Examples include appointment reminders, providing cash incentives, and identifying a local stakeholder to champion implementation. Discrete strategies are often packaged together (e.g., providing training as well as consultation) or protocolized (e.g., Getting to Outcomes, Collective Impact) in multifaceted and multilevel ways.

The ERIC taxonomy (Powell et al., 2015; Waltz et al., 2015) is the most comprehensive list of discrete implementation strategies available to reference. The taxonomy, comprising 73 discrete strategies grouped into nine categories, was developed from expert consensus. Limitations of ERIC have been discussed in the literature, and additional strategies have since been identified, so it is important to keep in mind that this work is ongoing.

Mechanisms

Mechanisms are processes that explain how implementation strategies operate on determinants to affect one or more implementation outcomes. The selection of strategies inherently relies on an implicit or explicit understanding of mechanisms (e.g., using training to address a knowledge/skill deficit), but this is still a developing area of IR (Lewis et al., 2020).

Expert advice

Distinguishing between evidence-based interventions and implementation strategies is not always easy. A few rules to guide your decision-making are:

-

- Strategies do not have an impact on individual health outcomes

- Strategies achieve implementation outcomes

- Strategies target and can operate on multiple levels in a delivery system

- The “THING” terminology is relative — it is usually an intervention but can also be a strategy if the strategy is the innovation being introduced into the system

If you are using CFIR as your determinant framework, use the CFIR-ERIC matching tool to generate a list of strategies to prioritize based on known CFIR determinants. The developers of this tool acknowledge that more research is still needed to better guide strategy choices and selection and encourage caution with the use of this tool.

Specification of implementation strategies in the literature is very poor, limiting reproducibility and generalizability across studies. Thus, it is essential that you clearly specify the strategies you select for your IR study. Proctor et al. (2013) recommend seven dimensions to specify: actor, action, action target, temporality, dose, implementation outcome, and justification.

Mechanisms are inherent in the justification of why you select certain strategies. Even though there is limited guidance in the field around mechanisms, it is important that your IR study presents an initial conceptualization of mechanisms. You can draw on theories of individual behavior change and organizational change to help specify these processes.

Action items

-

- Use methods such as intervention mapping, concept mapping, conjoint analysis, group model building, and user-centered design with your implementation partners to select and tailor implementation strategies for your context (Power et al, 2017).

- Engage with your implementation partners and consider how the strategies that you are selecting will address imbalances among target populations.

- Specify your strategies.

- The IRLM can help you organize these (see section titled Using Conceptual Frameworks and the IRLM for more information on this tool).

- Document adaptations to your strategies over time using tools like FRAME-IS (Miller et al., 2021) or the Longitudinal Implementation Strategy Tracking System (LISTS).

What it is

Strategies are activities or techniques used to enhance adoption, implementation, sustainment, and/or scaling of the THING. In other words, strategies are the stuff one does to help other people and places do the evidence-based THING. They often target the healthcare delivery system, and they do not have a direct effect on clinical outcomes. They are the central focus of IR.

A discrete strategy is a single action or activity that can impact implementation. This is the smallest “unit” of strategies. Examples include appointment reminders, providing cash incentives, and identifying a local stakeholder to champion implementation. Discrete strategies are often packaged together (e.g., providing training as well as consultation) or protocolized (e.g., Getting to Outcomes, Collective Impact) in multifaceted and multilevel ways.

The ERIC taxonomy (Powell et al., 2015; Waltz et al., 2015) is the most comprehensive list of discrete implementation strategies available to reference. The taxonomy, comprising 73 discrete strategies grouped into nine categories, was developed from expert consensus. Limitations of ERIC have been discussed in the literature, and additional strategies have since been identified, so it is important to keep in mind that this work is ongoing.

Mechanisms

Mechanisms are processes that explain how implementation strategies operate on determinants to affect one or more implementation outcomes. The selection of strategies inherently relies on an implicit or explicit understanding of mechanisms (e.g., using training to address a knowledge/skill deficit), but this is still a developing area of IR (Lewis et al., 2020).

Expert advice

Distinguishing between evidence-based interventions and implementation strategies is not always easy. A few rules to guide your decision-making are:

-

- Strategies do not have an impact on individual health outcomes

- Strategies achieve implementation outcomes

- Strategies target and can operate on multiple levels in a delivery system

- The “THING” terminology is relative — it is usually an intervention but can also be a strategy if the strategy is the innovation being introduced into the system

If you are using CFIR as your determinant framework, use the CFIR-ERIC matching tool to generate a list of strategies to prioritize based on known CFIR determinants. The developers of this tool acknowledge that more research is still needed to better guide strategy choices and selection and encourage caution with the use of this tool.

Specification of implementation strategies in the literature is very poor, limiting reproducibility and generalizability across studies. Thus, it is essential that you clearly specify the strategies you select for your IR study. Proctor et al. (2013) recommend seven dimensions to specify: actor, action, action target, temporality, dose, implementation outcome, and justification.

Mechanisms are inherent in the justification of why you select certain strategies. Even though there is limited guidance in the field around mechanisms, it is important that your IR study presents an initial conceptualization of mechanisms. You can draw on theories of individual behavior change and organizational change to help specify these processes.

Action items

-

- Use methods such as intervention mapping, concept mapping, conjoint analysis, group model building, and user-centered design with your implementation partners to select and tailor implementation strategies for your context (Power et al, 2017).

- Engage with your implementation partners and consider how the strategies that you are selecting will address imbalances among target populations.

- Specify your strategies.

- The IRLM can help you organize these (see section titled Using Conceptual Frameworks and the IRLM for more information on this tool).

- Document adaptations to your strategies over time using tools like FRAME-IS (Miller et al., 2021) or the Longitudinal Implementation Strategy Tracking System (LISTS).

Measuring Implementation Success (Outcomes)

What it is

Implementation outcomes are the effects of deliberate and purposive implementation strategies to implement the THING. They tell us how much and how well people implemented the THING and whether your IR study successfully helped address the implementation gap.

Two frameworks commonly used to guide the selection of implementation outcomes are the RE-AIM model (Glasgow et al., 2018) and Implementation Outcomes Model (Proctor et al., 2011).

Implementation outcomes serve three functions:

-

- Proximal indicators of implementation processes (e.g., number of providers that found the THING acceptable)

- Indicators of implementation success (e.g., number of providers who delivered the THING with fidelity)

- Indicators of implementation success (e.g., number of providers who delivered the THING with fidelity)

Implementation outcomes may be measured at different levels of implementation (patient/client, clinician/provider, /site), and there are many ways these outcomes may be measured (quantitative, organization qualitative, administrative data, audit of records). When and how frequently an implementation outcome is measured is often informed by the stage of the IR study.

Expert advice

-

- There are many different possible implementation outcomes to measure. It is common for an IR study to include many outcomes, but important outcomes vary by stage of IR.

- The HIV Implementation Outcomes Crosswalk helps identify and operationalize the outcomes of greatest relevance for your IR study.

- Consider the level in the delivery system that your strategy is in to select the appropriate outcome to evaluate that strategy. For example, if your strategy is to engage clinic leaders, that will likely have direct effects on clinic adoption (site level) and not effects on provider adoption (individual level), unless you are implementing provider-level strategies as well.

- Mettert et al. (2020) published a review of psychometric properties of implementation outcomes measures.

Action items

-

- Select implementation outcomes to measure in collaboration with your implementation partners and using the HIV Implementation Outcomes Crosswalk.

- Work with your implementation partners to design and select the methods to collect your implementation outcomes.

What it is

Implementation outcomes are the effects of deliberate and purposive implementation strategies to implement the THING. They tell us how much and how well people implemented the THING and whether your IR study successfully helped address the implementation gap.

Two frameworks commonly used to guide the selection of implementation outcomes are the RE-AIM model (Glasgow et al., 2018) and Implementation Outcomes Model (Proctor et al., 2011).

Implementation outcomes serve three functions:

-

- Proximal indicators of implementation processes (e.g., number of providers that found the THING acceptable)

- Indicators of implementation success (e.g., number of providers who delivered the THING with fidelity)

- Indicators of implementation success (e.g., number of providers who delivered the THING with fidelity)

Implementation outcomes may be measured at different levels of implementation (patient/client, clinician/provider, /site), and there are many ways these outcomes may be measured (quantitative, organization qualitative, administrative data, audit of records). When and how frequently an implementation outcome is measured is often informed by the stage of the IR study.

Expert advice

-

- There are many different possible implementation outcomes to measure. It is common for an IR study to include many outcomes, but important outcomes vary by stage of IR.

- The HIV Implementation Outcomes Crosswalk helps identify and operationalize the outcomes of greatest relevance for your IR study.

- Consider the level in the delivery system that your strategy is in to select the appropriate outcome to evaluate that strategy. For example, if your strategy is to engage clinic leaders, that will likely have direct effects on clinic adoption (site level) and not effects on provider adoption (individual level), unless you are implementing provider-level strategies as well.

- Mettert et al. (2020) published a review of psychometric properties of implementation outcomes measures.

Action items

-

- Select implementation outcomes to measure in collaboration with your implementation partners and using the HIV Implementation Outcomes Crosswalk.

- Work with your implementation partners to design and select the methods to collect your implementation outcomes.

Using Conceptual Frameworks and the IRLM

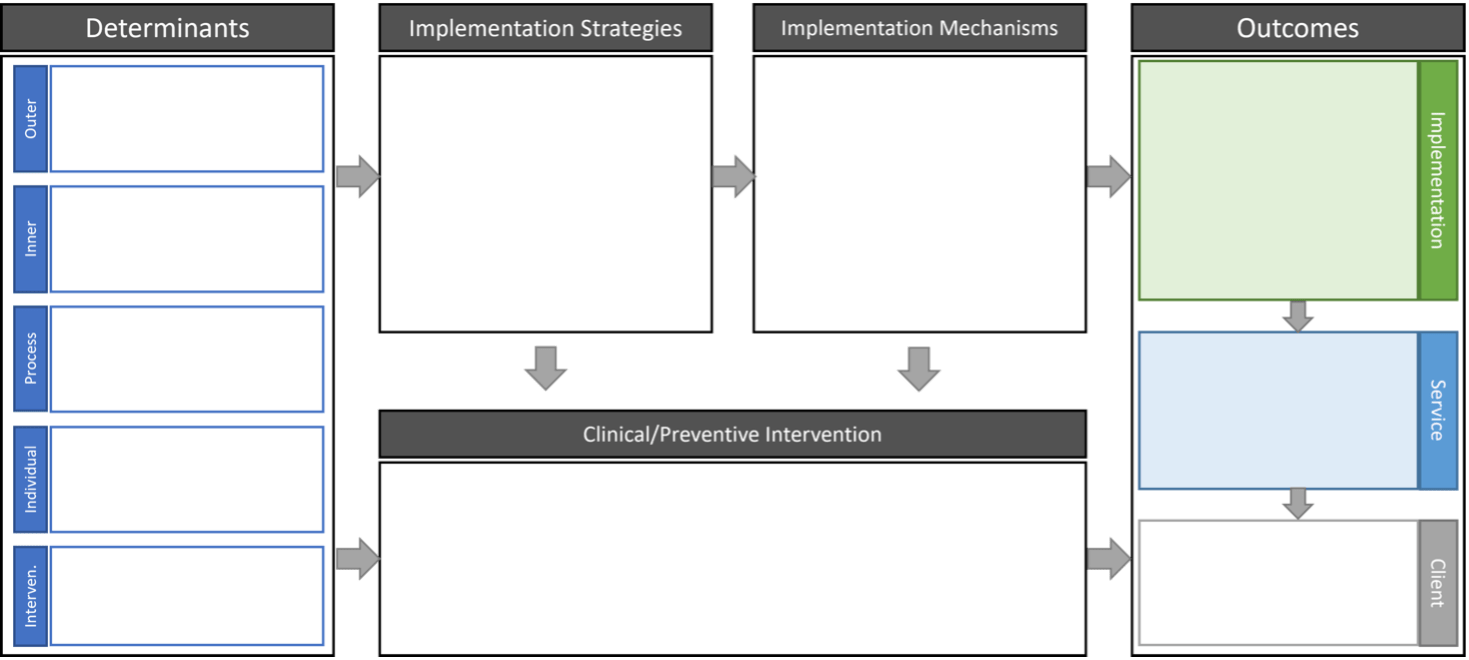

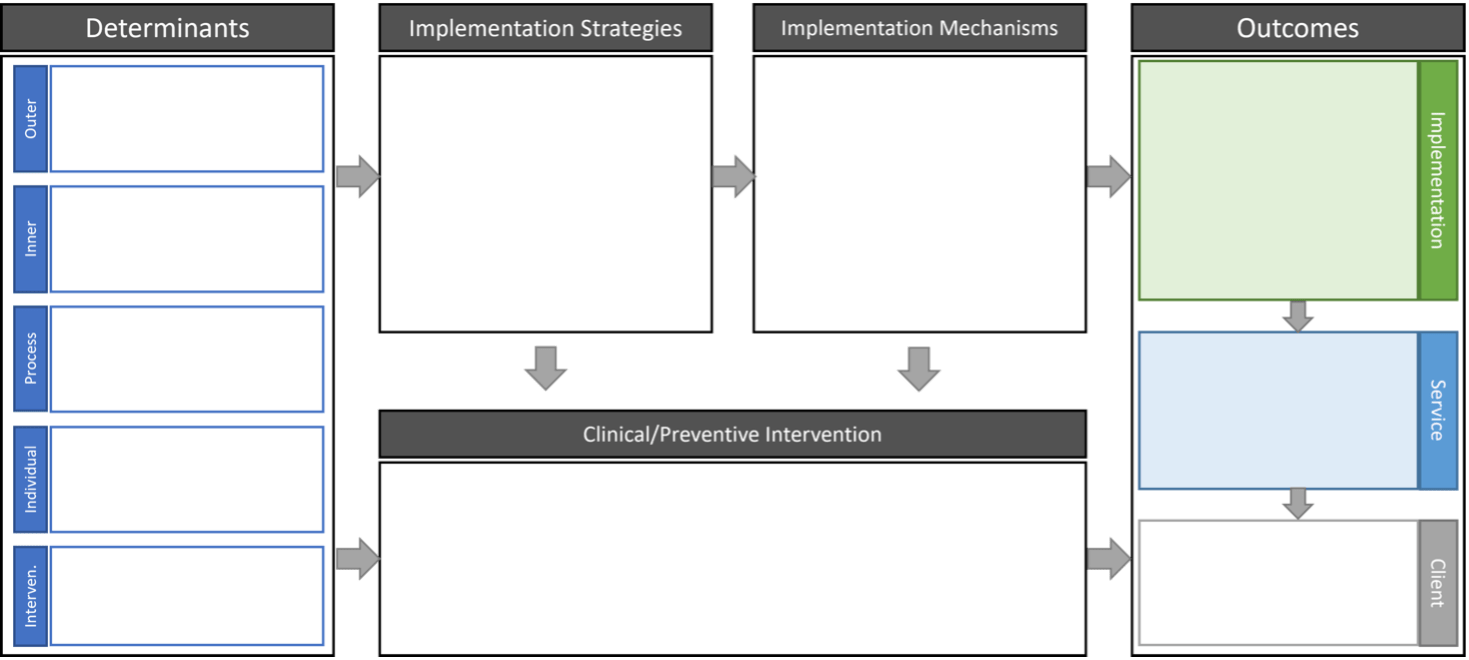

What it is

Conceptual Frameworks Research is strengthened when guided by conceptual frameworks. As evident throughout the previous sections, there are a myriad of theories, models, frameworks, and taxonomies (TMFTs) used to guide specification of different IR components. Because different TMFTs have different functions (Nielsen, 2015), one IR study often requires multiple TMFTs to guide each aspect of implementation (e.g., process, determinants, outcomes, strategies).

The Implementation Research Logic Model (IRLM)

The IR logic model is a trans-TMFT tool that helps combine and display multiple TMFTs for an IR study. It is also useful in specifying the relationships between different the different IR components. The IRLM is increasingly required by IR funding opportunity announcements and can be used for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing IR projects.

Expert advice

-

- For the average implementation researcher or practitioner, the distinction between the categories of theories, models, frameworks, and taxonomies is not significant. You can think of these terms interchangeably, with the caveat that each individual TMFT will vary in how abstract vs. specific and descriptive vs. explanatory it is.

- NIH reviewers of IR studies expect to see more than one TMFT and a sound justification for their selection.

- Many TMFTs of the same type describe similar constructs, so it is more important that you have all the right types of TMFTs to fit your IR study and less important that you select any one specific TMFT. You can select specific TMFTs within each type based on setting/context, familiarity, previous literature, etc. The website https://dissemination-implementation.org/ assists in helping you look for specific TMFTs.

Action items

-

- Select TMFTs for each component of your IR study and justify their selection.

- Use the ISCI IRLM resource page, with templates and guides for use, to develop your own IRLM. Engage with your implementation partners in its completion.

What it is

Conceptual Frameworks Research is strengthened when guided by conceptual frameworks. As evident throughout the previous sections, there are a myriad of theories, models, frameworks, and taxonomies (TMFTs) used to guide specification of different IR components. Because different TMFTs have different functions (Nielsen, 2015), one IR study often requires multiple TMFTs to guide each aspect of implementation (e.g., process, determinants, outcomes, strategies).

The Implementation Research Logic Model (IRLM)

The IR logic model is a trans-TMFT tool that helps combine and display multiple TMFTs for an IR study. It is also useful in specifying the relationships between different the different IR components. The IRLM is increasingly required by IR funding opportunity announcements and can be used for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing IR projects.

Expert advice

-

- For the average implementation researcher or practitioner, the distinction between the categories of theories, models, frameworks, and taxonomies is not significant. You can think of these terms interchangeably, with the caveat that each individual TMFT will vary in how abstract vs. specific and descriptive vs. explanatory it is.

- NIH reviewers of IR studies expect to see more than one TMFT and a sound justification for their selection.

- Many TMFTs of the same type describe similar constructs, so it is more important that you have all the right types of TMFTs to fit your IR study and less important that you select any one specific TMFT. You can select specific TMFTs within each type based on setting/context, familiarity, previous literature, etc. The website https://dissemination-implementation.org/ assists in helping you look for specific TMFTs.

Action items

-

- Select TMFTs for each component of your IR study and justify their selection.

- Use the ISCI IRLM resource page, with templates and guides for use, to develop your own IRLM. Engage with your implementation partners in its completion.

Designing the Evaluation

What it is

“Design” refers to the structure of the research study (e.g., methods, unit of analysis, randomization assignment, data collection points) used to systematically explore, examine, or evaluate implementation of the THING within target implementation settings. Because implementation studies ultimately aim to understand the effects of implementation strategies on selected implementation outcomes, the “design” is primarily influenced by how those strategies are specified: what, for whom, when, and where.

ImpSciUW.org provides an extensive overview of research methods and research designs used in IR.

Expert advice

Hybrid effectiveness–implementation approaches are often termed “designs,” but they only refer to the selection of outcomes for the study; an evaluation design is still needed. See Measuring Implementation Success (Outcomes) for more information.

Action items

-

- Select a design for your IR study.

What it is

“Design” refers to the structure of the research study (e.g., methods, unit of analysis, randomization assignment, data collection points) used to systematically explore, examine, or evaluate implementation of the THING within target implementation settings. Because implementation studies ultimately aim to understand the effects of implementation strategies on selected implementation outcomes, the “design” is primarily influenced by how those strategies are specified: what, for whom, when, and where.

ImpSciUW.org provides an extensive overview of research methods and research designs used in IR.

Expert advice

Hybrid effectiveness–implementation approaches are often termed “designs,” but they only refer to the selection of outcomes for the study; an evaluation design is still needed. See Measuring Implementation Success (Outcomes) for more information.

Action items

-

- Select a design for your IR study.

Funding IR

What it is

There are several ways to financially support (studying) implementation of the THING within target implementation settings. Three categories of projects that can be useful when considering what type of funding to pursue for your IR question are outlined below:

Implementation Research (IR):

-

- Projects that study the characteristics of new or existing implementation strategies with an emphasis on the evaluation of the strategy through implementation outcomes

- Testing two or more implementation strategies (discrete, multifaceted, blended) to implement a THING

Implementation Practice (IP):

-

- Evaluating implementation strategies with an emphasis on outcomes of a THING

- Projects that have a focus on quality improvement or program evaluation within a single or multiple implementation sites

- Dissemination or spread and scaling

- Projects that study well-supported EBPs and accompanying implementation strategies

The NIH IR funding PAR is: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-22-105.html

Examples of funded IR proposals can be found here:

https://impsci.tracs.unc.edu/get-funded/sample-grants/

https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/IS/sample-grant-applications.html

Expert advice

When writing an IR proposal, make sure to include the key ingredients detailed in the following guides:

-

- Proctor et al. (2012) provides a checklist of 10 key ingredients to make sure to include in the proposal

- Brownson et al. (2015) outlines what ingredients to include in each section of an NIH grant proposal (Aims, Significance, Innovation, Approach, Human Subjects) and the level of IS expertise needed to craft that section

Common pitfalls in writing IR proposals include:

-

- IR terminology/language not used correctly

- Study written with a clinical and lacks focus on implementation

- Team lacks IR expertise

- Study lacks clear description of the implementation problem (or how it aligns with methods)

- Lacks preliminary activities

- Engagement of implementation partners and evidence of collaboration lacking

- Organizational status, buy-in/commitment, generalizability

- Assessment of barriers and selection of feasible strategies

- Misuse of TMFTs (“square peg, round hole”)

- Not enough analytic power

Consider the multilevel nature of implementation strategies, how randomization will occur at higher-level units (e.g., clinic level), and how measurement will occur for each implementation outcome when estimating the power to detect an effect in your selected implementation outcomes.

Many Centers for AIDS Research/AIDS Research Centers have cores that can provide consultation on crafting an HIV-specific IR proposal. Some Centers for Translational Science Awards (CTSAs) also offer consultation for IR proposals.

Action items

-

- Identify a funding announcement that is a good fit for your IR question.

- Pursue pilot funding to conduct preliminary activities of your IR study (e.g., engagement of implementation partners, identification of barriers and facilitators).

- Seek review for your IR study. Work with your assigned IS Consultation Hub, if applicable. You may also contact us at isci@northwestern.edu, and we will attempt to identify support for your IR proposal.

What it is

There are several ways to financially support (studying) implementation of the THING within target implementation settings. Three categories of projects that can be useful when considering what type of funding to pursue for your IR question are outlined below:

Implementation Research (IR):

-

- Projects that study the characteristics of new or existing implementation strategies with an emphasis on the evaluation of the strategy through implementation outcomes

- Testing two or more implementation strategies (discrete, multifaceted, blended) to implement a THING

Implementation Practice (IP):

-

- Evaluating implementation strategies with an emphasis on outcomes of a THING

- Projects that have a focus on quality improvement or program evaluation within a single or multiple implementation sites

- Dissemination or spread and scaling

- Projects that study well-supported EBPs and accompanying implementation strategies

The NIH IR funding PAR is: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-22-105.html

Examples of funded IR proposals can be found here:

https://impsci.tracs.unc.edu/get-funded/sample-grants/

https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/IS/sample-grant-applications.html

Expert advice

When writing an IR proposal, make sure to include the key ingredients detailed in the following guides:

-

- Proctor et al. (2012) provides a checklist of 10 key ingredients to make sure to include in the proposal

- Brownson et al. (2015) outlines what ingredients to include in each section of an NIH grant proposal (Aims, Significance, Innovation, Approach, Human Subjects) and the level of IS expertise needed to craft that section

Common pitfalls in writing IR proposals include:

-

- IR terminology/language not used correctly

- Study written with a clinical and lacks focus on implementation

- Team lacks IR expertise

- Study lacks clear description of the implementation problem (or how it aligns with methods)

- Lacks preliminary activities

- Engagement of implementation partners and evidence of collaboration lacking

- Organizational status, buy-in/commitment, generalizability

- Assessment of barriers and selection of feasible strategies

- Misuse of TMFTs (“square peg, round hole”)

- Not enough analytic power

Consider the multilevel nature of implementation strategies, how randomization will occur at higher-level units (e.g., clinic level), and how measurement will occur for each implementation outcome when estimating the power to detect an effect in your selected implementation outcomes.

Many Centers for AIDS Research/AIDS Research Centers have cores that can provide consultation on crafting an HIV-specific IR proposal. Some Centers for Translational Science Awards (CTSAs) also offer consultation for IR proposals.

Action items

-

- Identify a funding announcement that is a good fit for your IR question.

- Pursue pilot funding to conduct preliminary activities of your IR study (e.g., engagement of implementation partners, identification of barriers and facilitators).

- Seek review for your IR study. Work with your assigned IS Consultation Hub, if applicable. You may also contact us at isci@northwestern.edu, and we will attempt to identify support for your IR proposal.

Want to stay up to date on implementation science and HIV research? Subscribe to our Interchange newsletter.

The Interchange is our biweekly newsletter that features implementation science news, research, trainings, events, and funding opportunities.